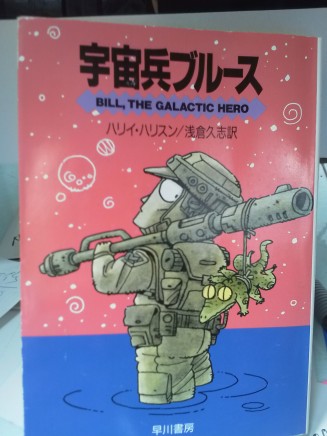

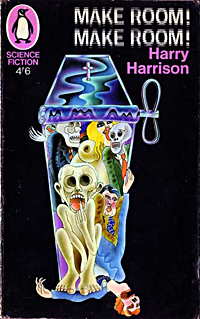

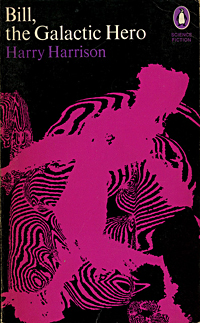

A nice write-up about the BILL project in the Boulder Weekly was picked up by USA Today, and with 22 Kickstarter days left, we’re more than half way to raising $100,000 to make the film of Harry Harrison’s immortal science fiction novel.

What is very noteworthy is that in the crowdfunding world none of the caveats of “film finance” seem to apply. For as long as I’ve been making features I’ve been told I can’t shoot them in black and white. “Audiences won’t stand for it” is a refrain film directors and cinematographers have been subjected to since the 1970s. “Television won’t accept it” was another frequently heard claim. Both were always demonstrably untrue since commercials and pop promos continued to be made in monochrome, and their only destination was the telly. Yet the caveat, for studios and British film funders, remained written in stone. Whereas not one of our 500+ backers has complained about the monochrome stock, or suggested we shoot the film in 120-fps 4K 3-D video instead. It’s almost as if Kickstarter backers have a clearer idea of what a film is, and what they want it to be, than Hollywood studio execs… Could this be so?

I have had a couple of enquiries about the student aspect of the production. One person is worried that the term “student film” has a negative connotation which could put supporters of the project off. This might be a valid point, but it isn’t something I’ve felt. I was a film student, at Bristol in England and at UCLA, and had a great education and a great time. At UCLA our role model was Charles Burnett, who had made, as one of his student projects, a black-and-white feature: KILLER OF SHEEP. When we shot REPO MAN I re-enrolled at UCLA so that we could use the video studio and the sound stages. Much of the work done at CU Boulder is technically and creatively of a very high standard: check it out here. So I reckon this attempt at making the biggest student film of all time is a plus, rather than a minus.

The other query was as to the ethics of getting students to work without pay on a feature film which may one day make money. This, too, is a fair point. No one working on BILL will get paid. The budget will be spent entirely on film stock, processing, props, costumes, visual effects materials, food, travel, and shipping out Kickstarter rewards. Most sane people in the middle of their lives cannot live this way. They need to be paid, to support their families, and homes, and cars. Only students, and those with a vocation, or a vacation, can create art without hope of pay.

What if BILL makes money? Let’s raise the budget first, and make the film, and hope it’s good and blessed with great fortune. Everyone who works on the film, as a crew person or an actor, including me, will receive one producer’s point. What will this be worth? Who knows? There are so many stages in the progress of a film. Finishing it is just part of the process. Getting it out and seen by an audience is another part. Happy retirement in a sunny fishing village is probably something else. Right now, one must concentrate on fundraising, and making the best film possible.

And on other things unrelated. For, as Harry wrote, “I know of no serious writer who does not need his solitude, his sitting and thinking time, in addition to his writing time.“